I would like to share my first-hand experience of accompanying aid workers from Save the Children during their visit in February 2021 to a village reeling from the effects of flooding in the state of Tabasco, Mexico.

From the moment we leave the city of Villahermosa, the water is ubiquitous. Countless puddles remain from the recent floods in Tabasco, accompanied by swamps that seem to thrive on these green plains stretching out at sea level. We cross the imposing Grijalba, Usumacinta and San Pedrito rivers that pour into the Gulf of Mexico, each one wider than any rivers I’d ever seen in this country. But when we leave behind the highway to turn on to a dirt track, the endless marshes seem to be stalking us less than three metres on either side of the car, furtively flanking the slender strip of land that, just a few weeks earlier, had been drowning under one metre of floodwater.

We are headed for a small fishing village located a few hours’ drive from the Tabasco state capital of Villahermosa. Lalo is driving today. He joined Save the Children in October 2020 when flooding left many communities isolated in the midst of the COVID–19 pandemic. We are accompanied by Israel, a Save the Children veteran of several years. That day I’m traveling with them so I can see first-hand how this NGO works to deal with especially trying situations.

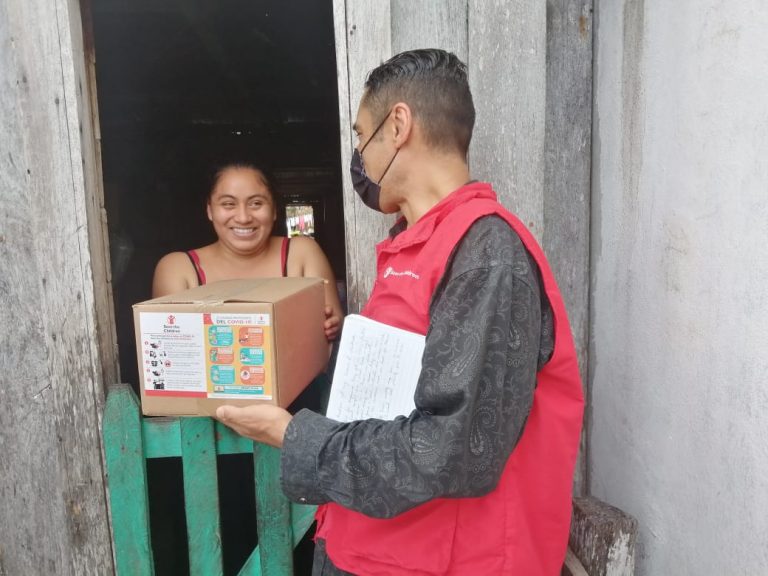

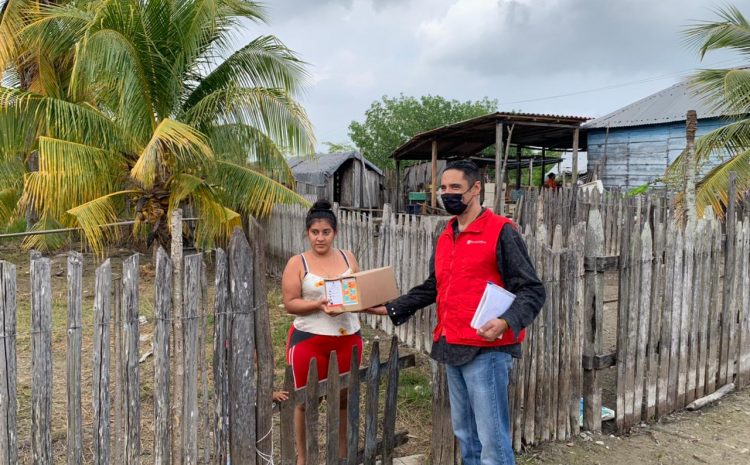

The last time Israel and Lalo came to this village – in December 2020 – they had to arrive on a small boat. On that occasion they brought food packages for the villagers; this time, the boxes we are carrying contain toilet paper, toothpaste and toothbrushes, soap, cloths for cleaning and some graphics

with information on good hygiene. We are bringing one box per home.

At first sight, the village is poor and tranquil. All the houses are made of wood and some of them are still inside the flooded areas. The abundant grey clouds offer a constant reminder of the not-so-constant levels of water in this part of the world. The shortages and general vulnerability faced by this small community become evident very quickly.

We start at the house of America, who lives with her six grandchildren: three girls and three boys. She describes how the family ran out of food due, first of all, to the impact of the pandemic and then because of flooding: “racoons got hold of chickens and turkeys. Now we live from what I earn selling the little fish they bring here.” America had been ill recently. “I was vomiting blood but there was no way for me to get to the doctor to find out what was wrong with me”, she pointed out. “All I had were traditional family remedies”.

A few houses further down the road, we spoke with Manuela, who lives with her son, her 13-year-old granddaughter and 11-year-old grandson. It’s a tough situation for her grandchildren. “School is closed and they have a hard time doing their

homework because they can’t catch a good signal for WhatsApp or we simply can’t afford for pay for the (internet) service. A teacher comes Monday to Thursday but my grandchildren have spent too much time indoors because of the floods.” She also told us that she had 30 chickens but they were all killed during the flooding.

Lack of food is a recurrent theme. All the men we spoke to in the village fish to feed their families and they all agree that there are now severe shortages of fish as a result of the floods. Miguel, father of six, notes: “now we just catch some shrimp, but there is no income. We only earn enough for two meals a day and we give priority to our children”.

Miguel also lost hens, chickens and ducks. Others had to put their cows down because they had nothing to feed them with and nowhere to keep them when water levels began to rise. The omnipresent stains about one metre above the ground on fences, walls and trees are evidence of the levels reached by the floodwaters between October 2020 and January 2021.

We progress house by house; we knock on every single door. The kits are often received with a smile and always with gratitude. The consensus among the villagers is that the basic products in these kits are hard to come by in this area and, when they are available, they don’t have enough money to buy them.

Many houses have been abandoned, including some that were inhabited as recently as December. The pandemic and the floods left many people with no choice other than to leave the village and head for other towns or even other states to look for work. It’s unlikely that they’ll ever return.

One thing that really stands out during out visit is the general mood of the inhabitants. From their clothes to their homes, everything would appear to suggest a very sparse and meagre lifestyle, with absolutely nothing to fall back on as a counterweight for the highly precarious economic and environmental conditions they live in. It is precisely circumstances like these that prompt many villages to join the rural exodus which, for the last few decades, has flooded the cities in the quest for some means of subsistence. Nonetheless, good humour and a general light-heartedness were very much in evidence that day. The villagers would describe their living conditions, but they never complained.

I left Tabasco with a sense of admiration for both the sheer resilience of its inhabitants and the efforts of Israel and Lalo as bearers of humanitarian aid and their message of hope and solidarity. But the strongest sensation was a profound feeling of gratitude for the things I have. This is why we should never hesitate when it comes to giving. At the end of the day, giving is an elevated act by which we infuse our own gratitude with life of its own.

If you would like to help Save the Children in their invaluable work with the poorest communities in Tabasco, click on “Make a donation”. For any contribution you make, there will be someone who is going to very grateful to receive it.